It is said that sowing a seed is an act of faith. Perhaps, then saving seeds is an act of hope. It symbolizes a belief in the future when the seeds can be sown again. Ensuring the future of food is one of the most life-affirming practices there can be. A seed simultaneously holds the wisdom of the past, and the promise of tomorrow encoded in its genetic make-up. Over thousands of years, our ancestors carefully selected traits that made a particular plant stronger, tastier, and more resistant to erratic weather or simply more beautiful to look at through saving seeds. In the age of commodified foods, it is easy to neglect the millennia of observation, experimentation, and knowledge encompassed in the edible plants we have today and the tiny miracle of the seeds they produce. Yet, they are central to the struggles and narratives of food sovereignty. This term was first coined in 1996 by an international farmers’ organization called Via Campesina, to emphasize their right to produce culturally appropriate foods using sound ecological methods; instead of following the unsustainable practices dictated by corporate regimes. Seed saving goes to the heart of the matter, in terms of ensuring that growers can breed and exchange diverse seeds, instead of depending on companies to sell them hybrid varieties every season.

Having previously volunteered at community farms, I have had the pleasure of saving seeds of many edibles every year and participating in the joy of receiving and giving seeds for growing. So, introducing myself at the seed-saving workshop organized by the Calgary Seed Library (CSL) at the Land of Dreams (LoD), really felt like discovering friends I hadn’t yet met. CSL is a grassroots voluntary organization comprising people of diverse ages and professions, united in their dream of equitable food security. They collect and save seeds that can be freely borrowed by growers, who are then encouraged to return seeds from their harvest, so the cycle can continue. It was heartwarming to hear Sean from CSL mention that the initiative had been rewarding and healing for the volunteers, most of whom are working in the environmental space and tend to feel burnt out. CSL is trying to expand their seed collection, especially to include varieties grown by immigrant growers and not easily found at commercial stores.

4 Steps to Seed Saving

Sean and Charlie began the workshop by handing out a cute bookmark summarizing broad steps to save seeds from any plant. They encouraged participants to look around and identify distinct kinds of seeds and how they might look for flowers, plants, tubers, and so on. They then went on to discuss how to figure out the right time to collect the seed. As a rule of thumb, the seed should be dry, hard, and mature. If it is a fruit, the fruit should be overripe and the plant nearly dead. If the seed is in a flower, the flower should be dry. A plant's final resources go towards producing the seed, and it is important to let the plant direct all its energy into creating healthy, viable seeds. When the seeds are ready for collection, they can be separated from the pod, fruit, or flower - as appropriate. The seeds should be saved in a cool, dry place in an airtight container, to prevent any condition that can kickstart germination. Generally, smaller seeds like those of radish, mustard, etc. can stay viable for a couple of years; while bigger seeds like corn, peas, etc. should be used in the next season. The germination rates and time for each plant vary, so it is good practice to get some information about the plant when sowing seeds in the next season.

Collecting Seeds at LoD

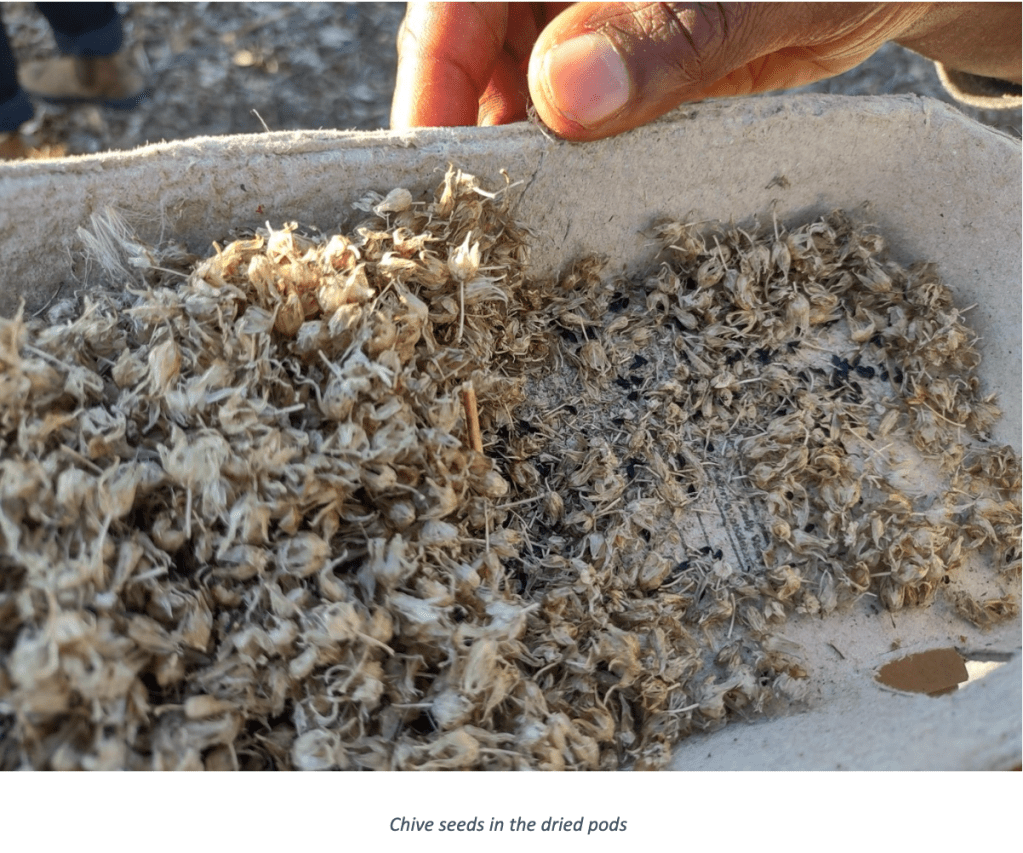

After the introduction, we decided to walk around and collect some seeds from a couple of plots at LoD. By then, more people from CSL joined us and we organically began mingling and talking to each other, while looking for dry seeds to collect. Janet from LoD mentioned that she had dried spinach plants and lovage flowers on her plot, so we went to gather them. We also found dried chives that we collected. While engaged in the task, I spoke to Chizobam, who has recently moved from Nigeria. She greatly appreciated the initiative and commented on how seed companies back home have been steadily disrupting the practice of saving local seeds. An avid grower, she explained how traditional varieties of many food crops are on the decline in Nigeria. Similar stories have played out across the world. India, once home to over 100,000 varieties of rice now struggles to maintain the presence of a few thousand varieties, of which just a handful are being cultivated for consumption commercially. Debal Deb, a plant scientist and activist who has been saving over 1000 rice varieties in India for decades, says:

“Seed represents culture. All seeds, not just rice. It’s Indigenous communities that carefully selected, bred, and adapted all the varieties of rice we consume today. To me, as an ecologist and scientist, the seed is the result of centuries of experience by ancient farmers who created these varieties to suit different climates, cultures, and contexts. To the farmers and Indigenous communities, it is an embodiment of food culture… If the farmers lose ownership of seeds and their sovereignty, they lose their knowledge as well. No company can replace it.”

(Source: https://agrowingculture.substack.com/p/reclaiming-culture-through-seeds)

All over, farmers and consumers lose agency regarding what to produce and consume if the agro-biological diversity is destroyed through a monopoly of the seed business. More urgently, monocultures are also particularly vulnerable under climate change. Resilience in food systems can only begin through supporting a diversity of crop varieties. Locally, if seeds are saved at LoD each year, each successive generation is better adapted to the climate, thus eventually creating a variety suitable for Calgary weather. This is even more important for crops that are not native to the area, and have a chance of adapting, if good seeds are saved every season.

Building Communities Through Shared Practices

After collecting seeds, we sat around a table to clean and sort them. Conversations and laughter flowed freely as people carefully separated the seeds, and I heard a grower Xochitl comment, “This is so relaxing!”

I ended up speaking with another volunteer at CSL, Greg, who has been supporting the collective in several ways and grows many varieties of tomatoes.

In the end, it felt satisfying to see jars of seeds fill up, ready to be packed into smaller packets for free distribution. It reminded me of the time I was facilitating a school terrace garden and saw a student describe her amazement at the number of seeds a single plant could produce.

Indeed, seeds embody the generosity and determination of a plant to continue living. Through respecting and preserving that abundance, we can live fruitful (pun intended!) lives too.

A Written Reflection by

-Deborah Dutta

Related video and readings for you to explore this topic further…

- https://www.seedthemovie.com/

- A seed is sleepy by Dianna Hutts Aston (Author), Sylvia Long (Illustrator)

- The seed savers by Bijal Vaccharajani

- One seed to another by Jude Fanton and Jo Immig

- One child, one seed by Kathyrn Cave

- The green sprout journey by Satoko Chatterjee