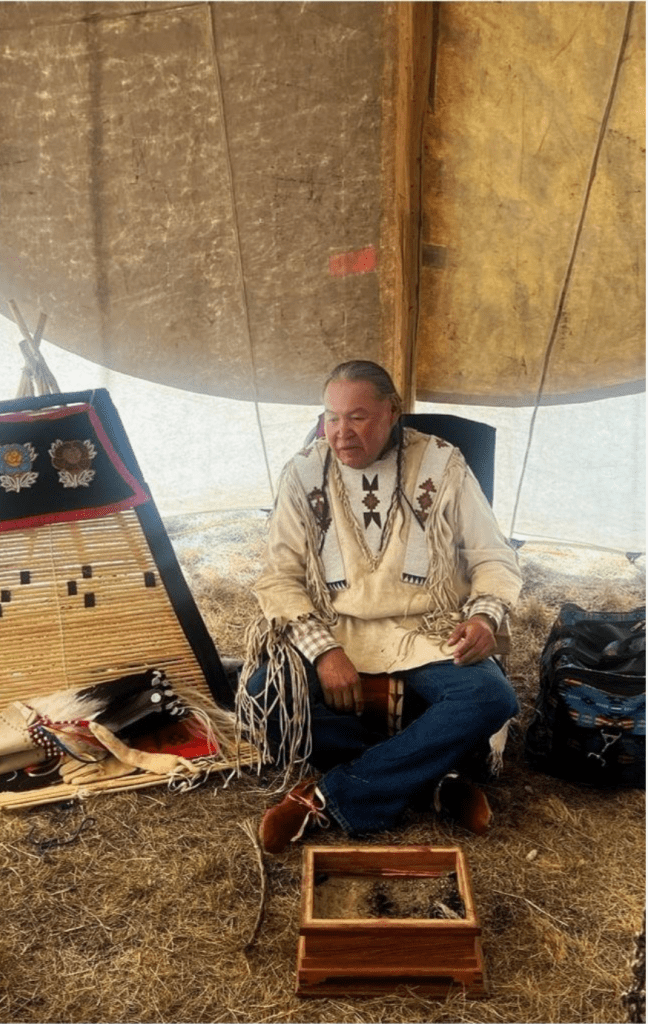

With the presence of Elder Herman Many Guns (Piikani/Blackfoot), it feels as though the air, time, and people move differently – with more intentions and thoughtfulness. Elder Many Guns has generously offered generational wisdom and teachings at the Land of Dreams community gatherings, where many of Soil Campers participated and learned. The Elder once said, “the soil is the most sacred thing.” We, as Soil Campers, learned from the Elder the significance of respecting the spirits of the soil and all living things in the soil. Also, we learned to see the soil as a partner, instead of seeing it as an object to extract from. “We came from clay and go back to clay,” Elder told us. At its core, human bodies need minerals that also compose the soil. There are also direct relationships between microbes living in human organs and those living in the soil. We came to see how the soil and humans are intimately connected.

As we redesign the Soil Camp pedagogy and program, Elder Many Guns’ wisdom, teachings, and hopes are central. To further our conversation, Elder Many Guns has invited us (Miwa Aoki Takeuchi, Mathew Swallow, Tatenda Mambo, and Sophia Thraya in Soil Camp Leadership Team) to the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump site. This visit opened my eyes and deepened the meaning of “land-based learning” – the visit afforded the opportunity for us to re-search, renew, and reexperience the meaning of land-based learning.

Estipah-skikikini-kots (in Blackfoot), or “Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump,” is a land inhabited and honoured by the Blackfoot People for at least 5700 years, perhaps over 10,000 years, until the occupation by the North West Mounted Police in 1874 under the settler-colonial project. The site was used for hunting buffalo, with culturally rich hunting techniques passed down from one generation to another by the Blackfoot People. In 1981, the site was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracting researchers from various disciplines and visitors from around the world. (More information about the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump is available in this open-access resource, “Buffalo Tracks: Educational and Scientific Studies from Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump”).

Elder Herman Many Guns is one of the few people who has lived closely with the land around the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump throughout his entire life. Before he became a respected Elder, he received a wide range of land-based teachings and was entrusted with Blackfoot Piikani transfer rights and songs. While adhering to community protocols on Blackfoot knowledge sharing, Elder Many Guns hopes that all newcomers to Turtle Island to fully understand the land, histories, and wisdoms of Indigenous Peoples.

Upon arriving at the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, we all experienced the power of generational land stewardship by the Blackfoot People — the scent of the air, the voices of wildlife, the colors of wild plants, and the sacred presence of the Buffalo Jump all conveyed the history of spiritual and physical stewardship. From generation to generation, Blackfoot people have lived with animals and plants in reciprocal ways. Even when they took the lives of buffalo to sustain their community, they honoured the spirits of buffalo through ceremony, and treasured every single part of buffalo. Blackfoot people traditionally never took too much to damage the ecology of the land, and they relocated the camp seasonally to minimize human-caused damages. They believed that the land provided all the vital offerings to sustain human lives and honoured the gifts they received for their food, medicine, clothing, tools, and housing.

The soil underneath the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump holds tens of thousands of stories of life, stretching over tens of thousands of years. As stories are the entry points for the spiritual world in Blackfoot teachings, according to Elder Many Guns, the world underground serves as the connector between the physical world we live in and the spiritual world.

This beautiful land has also borne witness to a brutal history of settler-colonialism. Iniiksii once roamed this land in herds, alongside Indigenous Peoples, in abundance. The massive and strategic slaughter of Iniiksii occurred around the time when treaties were forced upon Indigenous Peoples across Turtle Island. In the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump interpretive center, visitors will learn how colonizers slaughtered Iniiksii for extractive purposes from the North West Mounted Police’s winter coat to military purposes of making gunpowder. This strategic and colonial slaughter of Iniiksii, a significant source of nutrition and life and a culturally and spiritually significant symbol for Indigenous Peoples in Turtle Island, led to the near extinction of these sacred animals. Iniiksii, which once numbered as many as 50 million on the North American plains, are now reduced to a small herd.

The heart of land-based learning is to feel and connect with the histories and stories that the land has witnessed over tens of thousands of years. This connection is forged by being present and walking alongside Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers who embody songs, stories, and dreams rooted in the land. Simply inviting Indigenous Elders to enclosed school spaces is insufficient because their teachings are fundamentally intertwined with the land. There are teachings that cannot be experienced if they are detached from the land, the birthplaces of these teachings.

Land-based learning embraces both the beauty and the pain. While we marvel at the generational wisdom and knowledge that sustained Indigenous Peoples’ lives for over 10,000 years, we must also confront the brutal and violent histories of settler-colonialism. This dual understanding equips our current and future generations to strive toward a world free from the legacy of settler-colonialism. As Elder Herman Many Guns aptly said, “We are all given unique gifts.” Land-based learning should center on the journey of re-searching unique gifts given to us, listening carefully to the voices of the land. As we commit to this journey of re-searching, we can, hopefully, give back to the land meaningfully in our respective circles of influence.

Reflection written by Miwa Aoki Takeuchi, with permission from Elder Many Guns